- Prompt/Deploy

- Posts

- A Mental Model for Production AI

A Mental Model for Production AI

A four-layer framework for thinking about AI features in production.

Here's how I think about what it takes to ship AI features responsibly. The model part is rarely the hard part. It's everything around the model that determines whether your AI feature thrives or quietly falls apart. I wrote this for full-stack engineers who are navigating the shift - shipping AI into products and own it when it breaks. Writing it also helped me sharpen my own model; I'd love to hear how yours differs.

The Model Is Not the Hard Part

There's a moment in every AI feature project where the demo works. The model returns something impressive. Everyone gets excited. "Let's ship it!"

And then reality sets in.

McKinsey research puts it starkly: 90% of ML failures come not from developing poor models, but from "poor productization practices and the challenges of integrating the model with production data and business applications."

What follows is a framework for thinking—not a tutorial, not a tools guide, but a mental model I use when evaluating or building AI features. If I can't place a concern somewhere in this model, I figure I'm probably missing something. It's not one-size-fits-all: AI features vary in complexity, and which layers matter most depends on scope, what's at stake, and how much you're betting on the feature.

This is the first post in a series on Mental Models for Production AI. It's the map—subsequent posts will explore each region in detail.

The Simple Loop

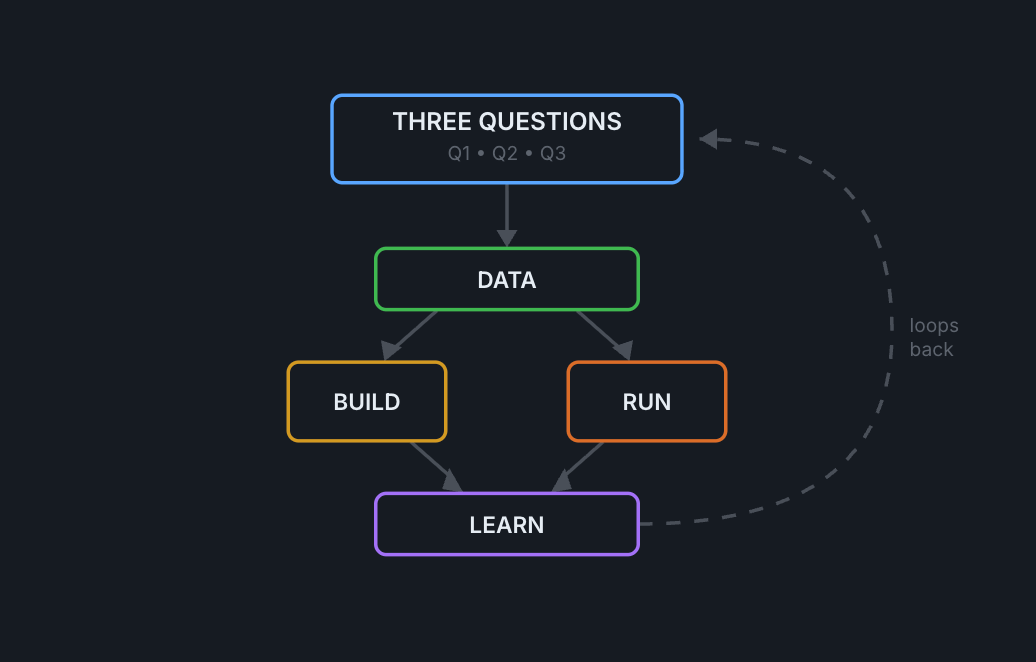

I find it useful to start with the simplest version. Here's how I see the basic flow:

The rhythm of production AI—not a one-time deployment, but a continuous cycle.

Three Questions → Data → Build/Run → Learn → (loops back)

This is the rhythm of production AI. It's not a waterfall where you deploy once and walk away. It's a cycle. The Learn phase feeds back into everything—new questions emerge, data needs change, systems need adjustment.

Why does this matter? Because systems that don't learn, decay. An AI feature that ships and never improves is already getting worse. The world changes. User behavior shifts. Data distributions drift. If you're not closing this loop, entropy wins.

The Four-Layer Model

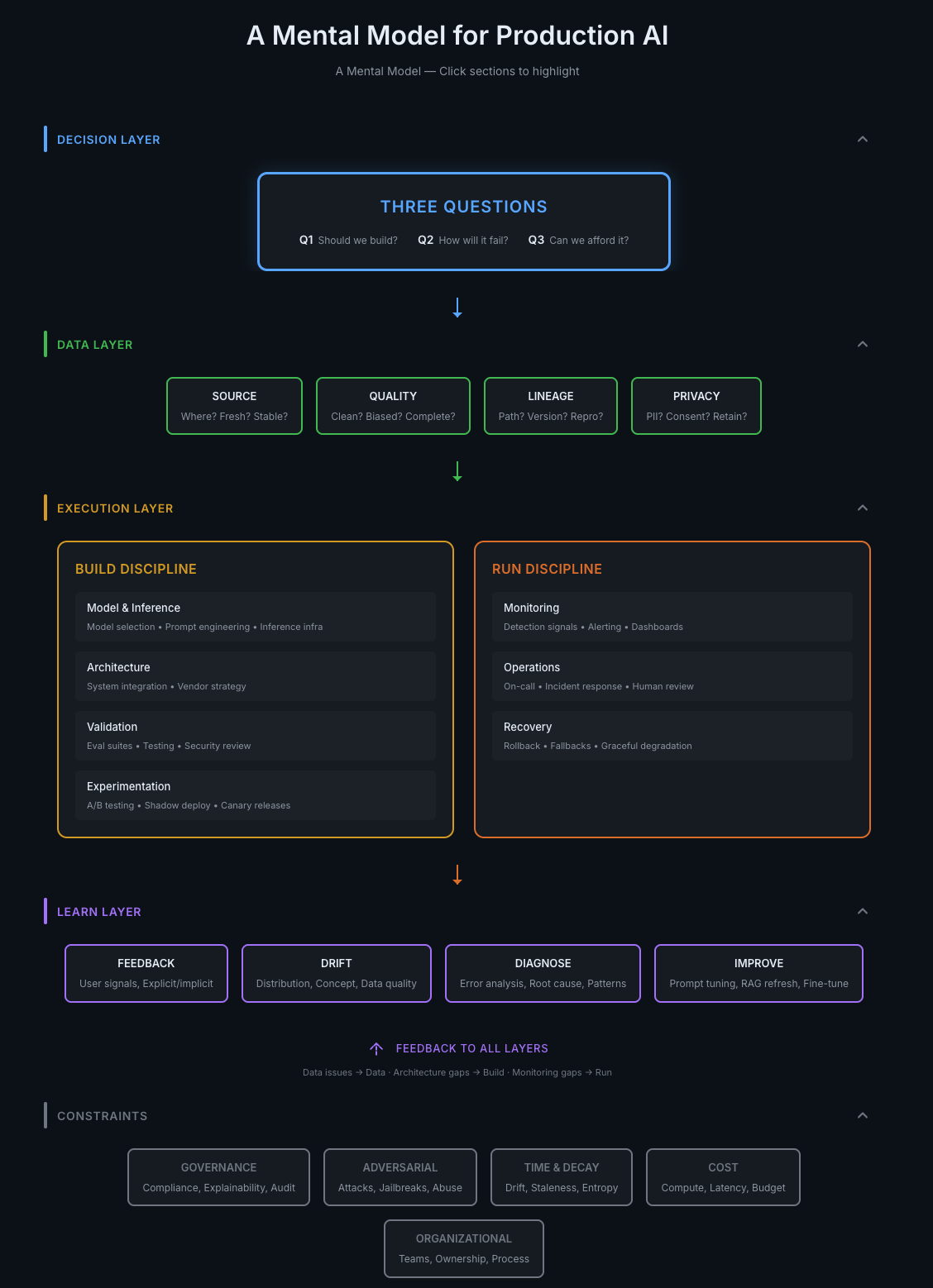

Now let's expand that simple loop into something more detailed. Each stage has layers of concern that are easy to miss if you're focused on just "making the AI work."

The full model. Each layer has distinct concerns. Skipping any layer doesn't save time—it creates technical debt or outright failure.

The four layers:

Decision Layer — The questions before you build anything

Data Layer — The foundation everything rests on

Execution Layer — Build it and run it (two different disciplines)

Learn Layer — Close the loop or decay

Plus: Constraints running underneath everything. Governance, security, cost, organizational factors—the gravity pulling on every decision.

Let's walk through each one.

Decision Layer: Three Questions Before Anything Else

I wouldn't want to start building without clear answers to three questions. They shape everything downstream.

Q1: Should we build this?

Is AI the right tool? Could something simpler work?

Anthropic's guidance on building agents captures this well: "Start with simple prompts, optimize them with comprehensive evaluation, and add multi-step agentic systems only when simpler solutions fall short."

The same applies to AI features generally. If a regex, a lookup table, or a deterministic rule would solve the problem, that's probably better than a probabilistic system that can hallucinate. I'm not saying "never use AI"—I'm saying the burden of proof should be on AI to justify its complexity.

Q2: How will it fail?

What does wrong look like? Can users tell when it's wrong?

This question matters because 90% of failures are architectural decisions, not model quality. The failure modes are predictable:

Context failures: The model is fine, but the surrounding system wasn't engineered for production

Data pipeline issues: Upstream changes have hidden downstream effects

Integration problems: The AI expects clean input but receives malformed data

Silent failures: Systems look "healthy" through dashboards while being confidently wrong

If I can't articulate how an AI feature will fail, I'm not ready to build it.

Q3: Can we afford it?

Not just today—at 10x scale.

In traditional MLOps, most of the cost is in training. In LLMOps, the cost shifts to inference. Every API call, every token, every GPU cycle in production adds up. Gartner estimates 40% of IT budgets are consumed by technical debt. With AI, that debt accumulates fast.

The question isn't "can we afford the prototype?" It's "can we afford this at scale, with monitoring, with failure handling, with iteration?"

Tip: The Three Questions Summary

Should we build this? — Is AI the right tool, or would something simpler work?

How will it fail? — What does wrong look like, and can users tell?

Can we afford it? — Not just today, but at 10x scale?

Data Layer: Your Ceiling

The way I think about it—your data quality is your ceiling. The model can't outperform what you feed it.

Four quadrants to consider:

Source: Where does the data come from? How fresh is it? How stable is the source? If your data comes from a third-party API, what happens when their format changes?

Quality: Is it clean? Is it biased? Is it complete? Garbage in, garbage out isn't just a cliché—it's the physics of ML systems.

Lineage: Can you trace any output back to its source data? Can you version it? Can you reproduce results from six months ago? When something goes wrong in production, lineage is how you debug it.

Privacy: How are you handling PII? Do you have consent for this use? What's your retention policy? GDPR fines can reach €20M or 4% of global revenue. This isn't optional.

Data pipeline issues are a common failure mode. A data engineer changes how a feature is computed upstream. Nothing breaks immediately. But three weeks later, model performance starts degrading, and nobody connects it to that pipeline change. Lineage prevents this.

Execution Layer: Build Discipline + Run Discipline

Here's where things get concrete. But I want to emphasize: building it right and running it right require different muscles.

Build Discipline

Model & Inference: Which model? What prompts? What infrastructure? Are you using a vendor API or self-hosting? These decisions compound.

Architecture: How does the AI integrate with your existing systems? What's your vendor strategy? Are you locked in or keeping options open?

Validation: Do you have eval suites? Are you testing beyond unit tests—actually testing the AI behavior? Have you done a security review for prompt injection?

Experimentation: Can you A/B test? Can you run shadow deployments where the AI runs but doesn't affect users? Can you do canary releases?

Run Discipline

Monitoring: What signals tell you something is wrong? Are you alerting on the right things? Dashboards are useless if nobody looks at them.

Operations: Who's on call? What's your incident response process? When do humans review AI outputs?

Recovery: Can you roll back in under a minute? What fallbacks exist if the AI fails? Does the system degrade gracefully or crash entirely?

A key insight from Google's MLOps documentation: "Only a small fraction of a real-world ML system is composed of the ML code." The supporting infrastructure—your Execution Layer—dominates production concerns.

Learn Layer: Close the Loop or Decay

An AI system that isn't learning is already getting worse. Here's what learning looks like in practice.

Feedback: User signals, both explicit (thumbs up/down, corrections) and implicit (engagement, abandonment, time-on-task). What are users telling you about quality?

Drift: Distribution drift (inputs look different than training data), concept drift (what "correct" means has changed), data quality drift (your sources are degrading). Drift detection is a core MLOps pattern.

Diagnose: Error analysis. Root cause identification. Pattern recognition. Why is the system failing in this specific way?

Improve: Prompt tuning. RAG refresh. Fine-tuning. Model swaps. The actual changes you make based on what you learned.

Notice the "Feedback to All Layers" arrow in the diagram. This is crucial: learning doesn't just improve the model. Data issues feed back to the Data Layer. Architecture gaps feed back to Build. Monitoring gaps feed back to Run. The Learn Layer is the mechanism that keeps the whole system healthy—it's how you avoid the slow decay that kills AI features over time.

Continuous training triggers include: scheduled retraining, new data availability, performance degradation detected. The specific triggers depend on your use case, but the principle is universal: you need triggers.

Constraints: What Runs Underneath Everything

I think of constraints as the gravity pulling on every layer. You can't ignore them, but you can plan for them.

Governance: Compliance requirements, explainability demands, audit trails. Regulated industries can't treat these as afterthoughts.

Adversarial: Attacks, jailbreaks, abuse. Prompt injection is a real risk. Your AI feature is an attack surface.

Time & Decay: Drift, staleness, entropy. Silent failures accumulate. Technical debt compounds. Systems that looked fine six months ago may be quietly degrading now.

Cost: Compute costs, latency requirements, budget constraints. Inference costs dominate in LLMOps. GPU scarcity affects what's even possible.

Organizational: Team structure, ownership clarity, process maturity. MLOps maturity models describe "Level 0" as manual processes with siloed teams—data scientists working in isolation, no automation, no reproducibility.

These constraints don't fit neatly into one layer—they pressure every layer simultaneously.

Putting It Together: Using the Model

I want to be clear: this is a map, not a checklist. Maps help you navigate; checklists tell you what to do. I'm conceptualizing a way to organize concerns, not a prescription.

How I use it:

Before starting: Walk through the Decision Layer questions. If the answers aren't clear, don't start building.

During planning: Check that each layer has a clear owner and plan. Who's responsible for data quality? Who's building the monitoring? Who decides when to retrain?

In production: Use the layers to diagnose where problems originate. Is this a data issue, a build issue, a run issue, or a learning issue?

When things break: Trace failure back through the layers. Most failures have roots in earlier layers than where they manifest.

I'm not claiming this is the only way to think about it. But it's how I organize the concerns when I'm evaluating or building AI features.

In future posts, we'll apply this model to specific scenarios and see how well the reasoning holds up.

The Map for What's Ahead

To recap: four layers (Decision, Data, Execution, Learn), one loop that connects them, and constraints running underneath everything. This post is the overview. The series will go deep into each area.

The goal is to make the invisible visible—to surface the concerns that trip teams up so you can address them intentionally rather than discover them in production.

Think about where your current or planned AI features sit in this model. Which layers are strong? Which layers are you guessing at?

Next up: Three Questions I'd Want Answered Before Building Any AI Feature—the Decision Layer in depth.

Reply