- Prompt/Deploy

- Posts

- The Multi-Agent Course Artifact Pipeline

The Multi-Agent Course Artifact Pipeline

Design a six-agent content pipeline that mirrors curriculum team roles, with explicit tool constraints, shared state contracts, and isolated evaluation for each stage.

In my experience developing engineering curriculum—I learned that content creation isn't one job, it's five. There's the person who interprets what learners need, the person who writes, the person who reviews code, the person who checks pedagogy, and the person who says "ship it." An agentic system should mirror that division of labor, not collapse it into one model call.

This post is part of the System Design Notes: Agentic Content Platforms for Technical Education series. This post designs the six-agent pipeline that maps to curriculum design stages: interpret → draft → validate → review → check → publish. We'll cover why separation of concerns matters for debuggability, how each agent's tools are intentionally constrained, and why RAG beats fine-tuning for educational content.

The Trap: Why One Agent Isn't Enough

The tempting first move is one agent. A single agent producing content is simpler to build, deploy, and reason about. It works—until quality drops and you can't figure out why.

Was it content accuracy? Broken code samples? Poor pedagogical scaffolding? With a monolithic agent, there's no way to isolate the failure. Every quality dimension is entangled in one model call, one prompt, one evaluation.

Separation of concerns is about debuggability. When a code validator silently passes broken imports because the sandbox has different dependencies than the learner environment, you need that failure isolated from content drafting and pedagogy

review. You can't fix what you can't isolate.

Consider a lesson that fails learner assessment. With one agent, you're debugging a black box. With separated agents, you ask targeted questions:

Did the Objective Interpreter produce clear, measurable outcomes?

Did the Content Drafter's RAG retrieval return relevant source material?

Did the Code Validator catch the import error?

Did the Pedagogy Reviewer flag the missing prerequisite?

Each question maps to a specific agent with explicit inputs, outputs, and evaluation criteria.

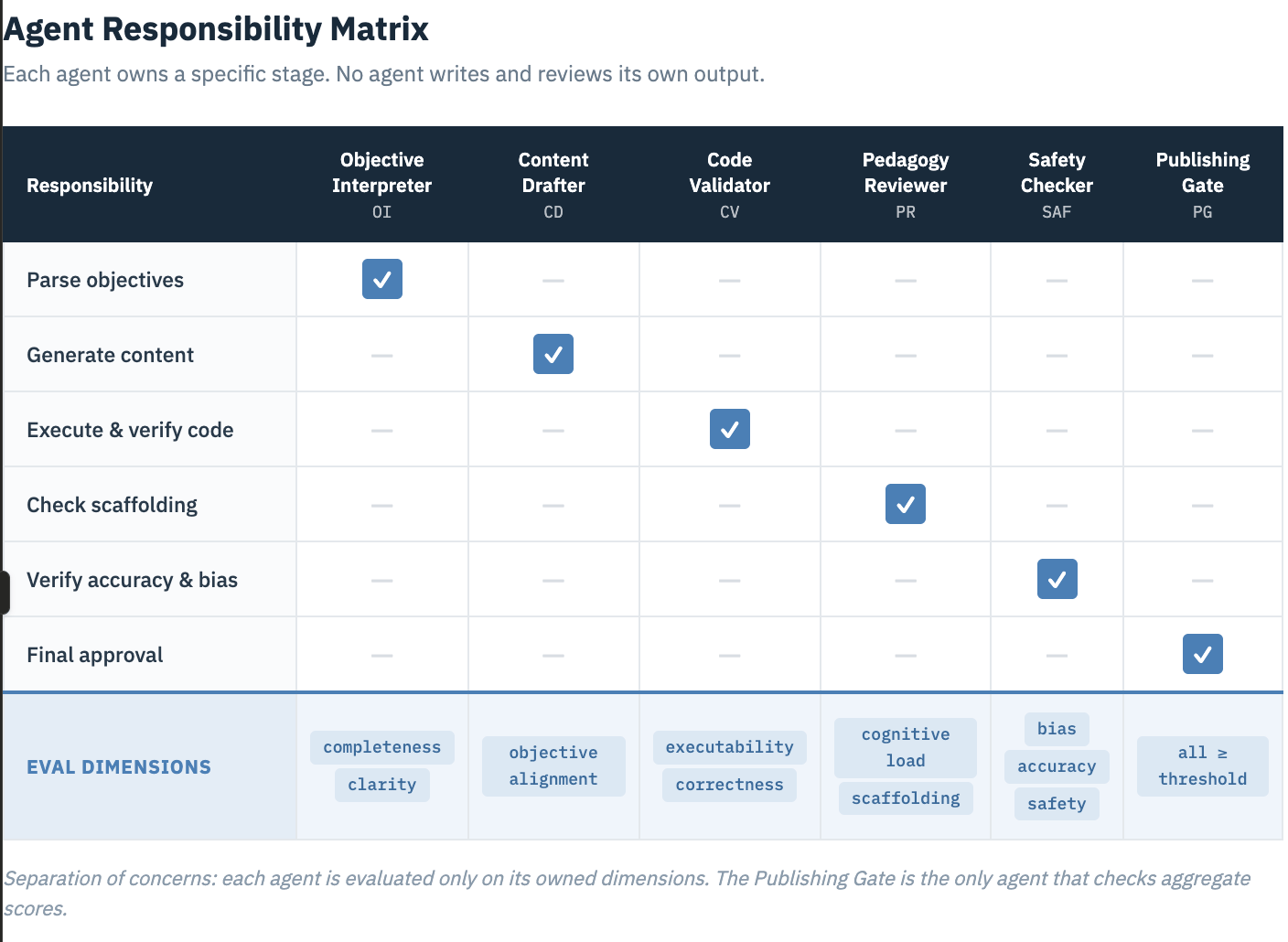

Six Agents Mapped to Curriculum Design Stages

The pipeline mirrors how content teams operate: interpret → draft → validate → review → check → publish.

Agent | Curriculum Stage | Inputs | Outputs | Eval Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Objective Interpreter | Requirements | Raw objectives, standards | Structured learning outcomes | Clarity, measurability |

Content Drafter | Writing | Outcomes, existing content | Draft lesson content | Accuracy, voice, scaffolding |

Code Validator | QA | Code samples | Validation results | Execution, correctness |

Pedagogy Reviewer | Review | Full draft | Pedagogy feedback | Prerequisite handling, cognitive load |

Safety Checker | Compliance | All content | Safety flags | Bias, accuracy, harm |

Publishing Gate | Release | Review artifacts | Publish decision | Human approval, completeness |

Each role has different expertise and failure modes. The Objective Interpreter fails when outcomes are vague or unmeasurable. The Content Drafter fails when technical details are wrong or scaffolding is missing. The Code Validator fails when

sandbox dependencies don't match learner environments. These are different skills requiring different evaluation rubrics.

Mapping to content-level rubric: The stage-level dimensions map to content-level evaluation rubric:

Accuracy → Technical Correctness

Execution/Correctness → Code Executability

Prerequisite handling → Prerequisite Alignment

Cognitive load → Cognitive Load.

Stage-level evaluation is more granular; content-level evaluation aggregates.

Each agent owns specific evaluation dimensions, enabling targeted debugging when quality drops.

Two Layers of Evaluation

This pipeline adds a layer of evaluation on top of the content-level rubric. The layers are complementary:

Layer | What's Evaluated | When | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

Stage-level | Each agent's output | After each pipeline stage | Agent-specific: clarity, execution, scaffolding, etc. |

Content-level | Assembled lesson | After pipeline completes | Rubric dimensions: Technical Correctness, Conceptual Clarity, Cognitive Load, Prerequisite Alignment, Code Executability |

Why both layers? Stage-level evaluation catches problems early—before they compound. A vague learning objective (caught at Objective Interpreter) is cheaper to fix than a vague lesson (caught at content-level review). But stage-level

evaluation can't catch emergent problems that only appear when components are assembled. A lesson might have clear objectives, accurate content, and working code, but still fail Cognitive Load when the pieces combine.

The content-level rubric remains the final gate. This pipeline's stage-level checks are optimizations—they reduce rework by catching failures earlier, but they don't replace the rubric evaluation.

Cost tradeoff: Stage-level evaluation adds LLM calls. For a single lesson, you're paying for: 6 agent calls + 6 stage-level evals + content-level evals. Three strategies reduce this cost:

Cheaper models for stage checks. Use Haiku or GPT-4o-mini for stage-level evaluation; reserve Sonnet/Opus for content-level. Stage checks are narrower—"did this code execute?"—and don't need frontier reasoning.

Conditional evaluation. Skip stage-level evals when the agent reports high confidence, or sample (evaluate 20% of outputs) rather than evaluating everything.

Fail-fast economics. If your Content Drafter fails 30% of the time, catching failures before running Code Validator, Pedagogy Reviewer, and Safety Checker saves 3 agent calls per failure. The break-even depends on your failure rate—high

rework rates justify early detection; low failure rates don't.

Start with content-level evaluation only, then add stage-level checks to specific agents with high failure rates.

The architecture uses a graph-based approach where each agent is a node and edges define how information and control move between agents. State is shared through an explicit schema.

from typing import TypedDict

from pydantic import BaseModel

class LearningOutcome(BaseModel):

objective_id: str

description: str

measurable_criteria: list[str]

class CodeSample(BaseModel):

language: str

code: str

expected_output: str

class ValidationReport(BaseModel):

passed: bool

results: list[dict]

errors: list[str]

class PedagogyReview(BaseModel):

cognitive_load_score: float

prerequisite_gaps: list[str]

scaffolding_feedback: str

class SafetyFlag(BaseModel):

dimension: str # "accuracy", "bias", or "harm"

severity: str

description: str

class PublishDecision(BaseModel):

approved: bool

reviewer_id: str

notes: str

class ContentState(TypedDict):

# Values are Pydantic model instances (BaseModel subclasses above).

# In production, serialize to dicts for checkpointing/persistence.

objective_id: str

structured_outcomes: list[LearningOutcome]

draft_content: str

code_samples: list[CodeSample]

validation_results: ValidationReport

pedagogy_feedback: PedagogyReview

safety_flags: list[SafetyFlag]

publish_decision: PublishDecision This schema is a contract. Each agent knows exactly what it reads and what it writes. The Objective Interpreter writes to structured_outcomes. The Content Drafter reads structured_outcomes and writes to draft_content and code_samples.

Agents should only write fields they own—but TypedDict and conventions alone don't enforce this at runtime. To prevent unauthorized writes, add a patch validator:

AGENT_WRITE_PERMISSIONS = {

"objective_interpreter": {"structured_outcomes"},

"content_drafter": {"draft_content", "code_samples"},

"code_validator": {"validation_results"},

"pedagogy_reviewer": {"pedagogy_feedback"},

"safety_checker": {"safety_flags"},

"publishing_gate": {"publish_decision"},

}

def validate_update(agent_id: str, update: dict) -> None:

"""Reject state updates to fields the agent doesn't own."""

allowed = AGENT_WRITE_PERMISSIONS.get(agent_id, set())

unauthorized = set(update.keys()) - allowed

if unauthorized:

raise ValueError(f"{agent_id} cannot write to: {unauthorized}")

Call validate_update in your orchestrator before applying any state patch. This catches bugs early and makes ownership violations explicit in logs.

State handoff uses a Command object that combines control flow and state updates:

from typing import TypedDict, Literal

from langgraph.types import Command

def content_drafter(state: ContentState) -> Command[Literal["code_validator"]]:

# Generate draft content with RAG

draft = generate_with_rag(state["structured_outcomes"])

code_samples = extract_code_samples(draft)

return Command(

goto="code_validator",

update={

"draft_content": draft,

"code_samples": code_samples

}

)

The Command specifies both the destination agent and the state updates. This makes the data flow explicit—you can trace exactly what information moves between agents.

Each handoff transforms specific data types, with explicit contracts at each boundary.

Constrained Tools: What Each Agent Cannot Do

Agents have explicit tools, not general-purpose capabilities. Constraints are intentional.

Agent | Can Use | Cannot Use |

|---|---|---|

Objective Interpreter |

| Any generation tools |

Content Drafter |

| Code execution, publishing |

Code Validator |

| Content modification |

Pedagogy Reviewer |

| Content generation |

Safety Checker |

| Any modification tools |

Publishing Gate |

| Any content tools |

The Content Drafter cannot execute code—that's the Code Validator's job. The Safety Checker cannot modify content—it can only flag issues. These constraints prevent agents from overstepping their expertise and ensure failures are isolated to the

responsible agent.

Enforcement mechanism: Python class properties don't prevent an agent from calling arbitrary functions—the tools property is declarative, not enforcing. Actual enforcement happens in the orchestrator's tool router:

class ToolRouter:

"""Routes tool calls and enforces per-agent allowlists."""

def __init__(self, tool_registry: dict[str, Callable]):

self.registry = tool_registry

def execute(self, agent_id: str, tool_name: str, args: dict) -> Any:

allowed = AGENT_TOOL_PERMISSIONS.get(agent_id, set())

if tool_name not in allowed:

raise PermissionError(f"{agent_id} cannot use tool: {tool_name}")

return self.registry[tool_name](**args)

The base class below declares intent; the tool router enforces policy:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from typing import Callable

class ContentAgent(ABC):

"""Base class for all content pipeline agents."""

@property

@abstractmethod

def tools(self) -> list[Callable]:

"""Tools this agent can use."""

pass

@property

@abstractmethod

def eval_dimensions(self) -> list[str]:

"""Evaluation criteria for this agent's output."""

pass

@property

@abstractmethod

def reads_from(self) -> list[str]:

"""State fields this agent reads."""

pass

@property

@abstractmethod

def writes_to(self) -> list[str]:

"""State fields this agent writes."""

pass

class ContentDrafterAgent(ContentAgent):

@property

def tools(self) -> list[Callable]:

return [

self.retrieve_similar_lessons,

self.generate_section

]

@property

def eval_dimensions(self) -> list[str]:

return ["accuracy", "voice_consistency", "scaffolding_quality"]

@property

def reads_from(self) -> list[str]:

return ["objective_id", "structured_outcomes"]

@property

def writes_to(self) -> list[str]:

return ["draft_content", "code_samples"]

This structure makes agent boundaries explicit. During debugging, you know exactly which tools were available, what state was read, and what was written.

Each agent has explicit capabilities and explicit restrictions, preventing scope creep.

Why RAG for the Content Drafter (Usually)

The Content Drafter uses RAG (retrieve_similar_lessons) rather than a fine-tuned model—but this isn't a universal rule. The choice depends on your constraints:

Factor | Prefer RAG | Prefer Fine-Tuning | Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

Content freshness | Fast-changing (APIs, libraries) | Stable (fundamentals, style guides) | Mixed curriculum |

Attribution needs | Citations required | Style/tone, not facts | Facts + brand voice |

Query volume | Lower QPS, variable topics | High QPS, repeated patterns | Varies by content type |

Latency tolerance | Seconds acceptable | Sub-second required | Cache hot paths |

Budget | Per-query retrieval costs | Upfront training, lower inference | Optimize by content tier |

For this pipeline, RAG wins because:

Dynamic knowledge. Curriculum changes frequently. New libraries emerge, APIs get deprecated, best practices evolve. As orq.ai notes, "unlike RAG, which dynamically queries external data sources, a

fine-tuned model is locked into the knowledge it was trained on." Retraining for every curriculum update is impractical.

Attribution requirements. Educational content needs traceable references. When a lesson claims "React 19 introduces use() for promise resolution," you need to trace that claim back to documentation or source material. RAG provides this

lineage; fine-tuned knowledge is opaque.

Cost at our scale. Fine-tuning costs are typically higher for frequently-changing content at moderate query volumes. orq.ai's analysis found "the overall cost of fine-tuning is much higher than RAG since it requires more labeled data and

more computational resources." At very high QPS with stable content, this calculus can flip.

The tradeoff is latency and retrieval quality. RAG adds retrieval time, and noisy retrieval can increase hallucinations by surfacing irrelevant context. For educational content where correctness is paramount, a lesson taking 30 seconds to

generate with accurate citations beats a lesson generated in 2 seconds with hallucinated facts. (Real-time tutoring has different constraints—there, you might accept cached or pre-generated content to meet latency requirements.)

Here's the RAG tool with a strict schema (shown in Anthropic/Claude tool format—LangChain uses a similar structure with @tool decorators):

tools = [

{

"name": "retrieve_similar_lessons",

"description": "Retrieve pedagogically similar lesson content from the curriculum database",

"input_schema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"objective_id": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The learning objective ID to find similar content for"

},

"max_results": {

"type": "integer",

"description": "Maximum number of similar lessons to return",

"default": 5

}

},

"required": ["objective_id"]

}

}

]

When might fine-tuning make sense? For consistent pedagogical voice—the tone and style that defines your brand. A hybrid approach might use RAG for curriculum knowledge with a fine-tuned base model for voice consistency. But this is an

optimization, not a starting point.

The Code Validator: Sandbox Architecture

Running LLM-generated code directly on your servers is risky. As Amir Malik documents, "It can leak secrets, consume too many resources, or even break important systems."

Threat model: What are you defending against?

Secrets exfiltration: Code that reads environment variables, mounted credentials, or cloud metadata endpoints

Resource abuse: Crypto miners, fork bombs, memory exhaustion

Lateral movement: Network calls to internal services, container escape attempts

Docker alone is not a security boundary—it's a packaging format with some isolation. Defense in depth requires: no network egress (or strict allowlists), read-only filesystem with temp-only writes, cgroup limits on CPU/memory/PIDs,

and seccomp/AppArmor profiles restricting syscalls. For higher assurance, use gVisor or Kata Containers to add kernel-level isolation.

Three sandbox approaches work for educational content:

gVisor provides user-space kernel isolation by intercepting system calls. It's the strongest isolation but adds operational complexity.

Docker containers offer pre-configured environments with resource limits. This is the most common approach for educational platforms because container images can match learner environments exactly.

Kubernetes Agent Sandbox provides a declarative API for managing isolated pods with stable identity. This works well for platforms already running on Kubernetes.

The critical insight: your sandbox must match the learner environment exactly. The most common code validation failure is dependency mismatch—code passes in the sandbox but fails for learners because they have different package versions.

Use identical Docker images. If learners run python:3.11-slim with pandas==2.0.3, your sandbox should use the same image.

Resource limits prevent runaway processes. A 1-second CPU limit catches infinite loops. A 64MB memory limit catches memory leaks. These constraints should be stricter than what learners experience—marginal code that passes at the limit will fail

for learners with slower connections or shared compute resources.

Safety Checker: Beyond Harm Detection

Content safety for education requires three dimensions, not just one.

Accuracy. Is the technical content correct? Educational platforms have a higher bar than general content. A blog post with a minor technical error is embarrassing; a lesson with a technical error teaches learners the wrong thing.

Benchmark-inspired test sets (TruthfulQA-style adversarial prompts designed to elicit false claims) help evaluate tendency to generate misleading information. Note that check_accuracy needs operationalization beyond LLM

self-assessment—implement retrieval + citation verification, or formal checks against authoritative sources, with human audit sampling.

Bias. Does content reinforce stereotypes? Examples matter in education. If every code sample uses "John" and "Mike" as variable names, or every database example uses traditionally Western names, learners notice. ToxiGen-like bias probes test

for implicit bias across demographic groups—these are evaluation datasets, not turnkey solutions.

Harm. Standard content moderation—is the content inappropriate for learners? This is the baseline, not the complete picture.

LLM-as-judge catches issues fast but inherits model bias. As Evidently AI notes, "cross-checking with humans and controlled test sets is necessary."

The evaluation layers: component-level checking (each agent's output) plus system-level checking (the integrated content). A lesson might pass safety checks at each stage but create problematic patterns when assembled.

Human-in-the-Loop: The Publishing Gate

Human oversight isn't optional for educational content. Learner trust requires that a human said "this is ready."

LangGraph's interrupt() function pauses graph execution and returns a value to the caller. The Publishing Gate uses this to require human approval:

from typing import Literal

from langgraph.types import interrupt, Command

def publishing_gate(state: ContentState) -> Command[Literal["publish", "revise"]]:

"""Require human approval before publishing."""

# Compile review summary for human

review_summary = {

"content_preview": state["draft_content"][:500],

"code_validation": state["validation_results"],

"pedagogy_score": state["pedagogy_feedback"].cognitive_load_score,

"safety_flags": state["safety_flags"],

"outstanding_issues": [

f for f in state["safety_flags"]

if f.severity == "high"

]

}

# Pause for human decision

decision = interrupt(review_summary)

if decision["approved"]:

return Command(

goto="publish",

update={

"publish_decision": PublishDecision(

approved=True,

reviewer_id=decision["reviewer_id"],

notes=decision.get("notes", "")

)

}

)

else:

return Command(

goto="revise",

update={

"publish_decision": PublishDecision(

approved=False,

reviewer_id=decision["reviewer_id"],

notes=decision["revision_notes"]

)

}

)

Three HITL patterns apply to educational content:

Approval gates: Pause before publish, route based on human decision. This is the Publishing Gate pattern above.

Review and edit: Surface the draft, accept an edited version as the resume value. Useful when humans need to make direct corrections.

Tool call interception: Embed interrupts within tool functions for approval workflows. Useful for high-stakes operations like database updates.

Implementation requires a checkpointer for state persistence and thread IDs for session tracking. Without persistence, you can't resume after the human decision.

Framework Comparison: Custom vs LangGraph vs CrewAI

Before building custom orchestration, four questions:

Is agent orchestration core to your product differentiation? Probably not. The pedagogy and evaluation system are the differentiators—the orchestration is plumbing.

Do you need deep customization of the orchestration layer? Maybe. HITL routing and eval-gate integration are specialized, but frameworks are adding these patterns.

Can your team maintain custom orchestration long-term? Depends on team size. A 3-person team should not own custom orchestration.

Is data too sensitive for third-party frameworks? Learner data and content IP flow through the pipeline. Evaluate each framework's data handling.

Dimension | LangGraph | CrewAI | Custom |

|---|---|---|---|

Learning curve | Steeper, explicit state management | Gentler, role-based definitions | Highest, full ownership |

Observability | LangSmith integration, widely-used tracing UI | AMP Suite or custom monitoring | Build your own |

HITL integration | Native | Less explicit patterns | Full control |

Production readiness | v1 positioned as stability-focused release | Good for MVPs/POCs | Depends on team |

Team size fit | Larger teams benefit from structure | Smaller teams benefit from velocity | Requires maintenance capacity |

Here's the same agent definition in both frameworks:

LangGraph:

from typing import TypedDict, Literal

from langgraph.types import Command

class ContentState(TypedDict):

# Simplified example—production version uses richer types

objective_id: str

draft_content: str

code_samples: list[str]

validation_results: dict

def content_drafter(state: ContentState) -> Command[Literal["code_validator"]]:

draft = generate_with_rag(state["objective_id"])

return Command(

goto="code_validator",

update={"draft_content": draft, "code_samples": extract_code(draft)}

)

CrewAI:

from crewai import Agent

content_drafter = Agent(

role="Content Drafting Specialist",

goal="Generate accurate, well-scaffolded lesson content",

backstory="Expert in technical writing with deep curriculum knowledge",

tools=[retrieve_similar_lessons, generate_section],

allow_code_execution=False, # Explicit constraint

max_iter=10,

respect_context_window=True

)

LangGraph makes state explicit; CrewAI makes roles explicit. Both enforce the same separation of concerns—the patterns matter more than the framework.

What This Architecture Enables

Whether you call these "agents" or "workflow nodes with LLM calls" is semantic—the value is stage isolation and eval gates, not the terminology. Critics of "multi-agent" framing have a point: these aren't autonomous entities negotiating with

each other. They're specialized processors in a pipeline. The architecture's benefits don't depend on the label.

Separation of concerns enables three things that monolithic agents cannot provide.

Targeted evaluation. Each agent has explicit eval dimensions that map to the content-level rubric from Evaluation-First Agent Architecture for Learning Outcomes. When accuracy drops, you know to look at the Content Drafter's RAG retrieval—and you know it will show up as a Technical Correctness failure in content-level evaluation. When code

samples break, you know to check sandbox dependencies—and you know it will show up as a Code Executability failure. Stage-level evaluation tells you where to look; content-level evaluation tells you what failed.

Parallelization. Agents without dependencies can run concurrently. The Safety Checker can run in parallel with the Pedagogy Reviewer—they read the same input and write to different state fields. The orchestration layer handles this

automatically. Caveat: parallel stages must produce commutative, merge-safe patches to state—if two agents write overlapping fields, you need either sequential execution or a reducer function to merge results deterministically. Note that

multi-agent pipelines accumulate token costs across agents; monitor cumulative usage and consider caching RAG results for frequently-referenced learning objectives.

Iteration. You can swap one agent without rewriting the pipeline. When a better code validation approach emerges, you replace the Code Validator. The state contract stays the same; other agents don't change.

💡 Tip: Start with sequential execution and add parallelization after you've validated the pipeline works end-to-end. Parallel debugging is harder than sequential debugging.

The objection is fair: this is more complex than one agent. One agent can produce educational content. But when quality drops—and it will—you'll want the isolation that separation of concerns provides.

Where This Leads

The evaluation rubric from the previous post maps directly to agent eval dimensions. Accuracy metrics evaluate the Content Drafter. Code correctness

evaluates the Code Validator. Prerequisite handling evaluates the Pedagogy Reviewer. The pipeline operationalizes the rubric.

ℹ️ Note: This post assumes familiarity with evaluation-first agent architecture design for learning outcomes. If you haven't read it, the eval

dimensions in the agent table may seem arbitrary—they're not.

Next in the series: The next post covers stateful orchestration—event-driven coordination, failure isolation, idempotency, and observability for running

this pipeline in production.

Further Reading

LangGraph Multi-Agent Orchestration Guide —

Comprehensive patterns for graph-based agent architecturesCrewAI Multi-Agent Systems Tutorial — Role-based agent definitions and separation of concerns

RAG vs Fine-Tuning Tradeoffs — Decision framework for dynamic content systems

Code Sandboxes for LLM AI Agents — Sandbox architecture options for code execution

LLM Safety and Bias Benchmarks — Content safety evaluation frameworks

Reply